By Brian Rogal, Bisnow Chicago

Whether or not a coronavirus vaccine becomes widely available in 2021, the 2020 economic crisis will damage efforts to create much-needed affordable housing in Chicago. Many of the subsidies that fuel the production and preservation of affordable units in the city come from private developers building market-rate homes, and with that construction slowing down, affordable developers may have to tighten their belts.

“Affordable housing is intertwined with the rest of the industry, and right now there is some faltering in the industry, which we are not immune to,” Theå Habitat Co. Senior Vice President Charlton Hamer said.

What makes the situation more complicated is that the economic crisis is also boosting demand for affordable housing. Although well-paying office jobs have mostly been preserved by new work-from-home strategies, unemployment has soared among low-income workers in service industries, reducing many households’ ability to pay market-rate rents, according to Hamer, who oversees Habitat’s 13,000-unit affordable housing portfolio.

“It’s hard to tell what will happen in Chicago in the short term, but the need will be even greater with less resources,” he said.

The pandemic is making the housing situation precarious throughout the nation.

“Cities are facing an unprecedented crisis right now,” Standard Cos. principal and co-founder Jeff Jaeger said.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot came into office promising to boost affordable housing production and strengthen the flow of resources to low-income communities on the South Side and the West Side.

Her 2021 budget seems to uphold that commitment. Even though the sharp decline in tax revenues helped open up a $1.2B deficit, Lightfoot’s October budget did not include cuts to affordable housing programs and even included a $2M boost. Instead, the mayor proposed a property tax hike and eliminating nearly 2,000 jobs, among other cost-cutting measures, to close the deficit. The City Council will hold a final vote on the proposal Tuesday.

“They have tried hard every year to get all the resources out the door that they can, and I’m not sure we can ask any more of them than that,” said Bill Eager, senior vice president of Preservation of Affordable Housing, a national nonprofit developer that acquires and develops affordable properties in Chicago and many other cities.

But the city already has a shortage of 120,000 affordable homes, according to data from the city of Chicago, and existing programs struggle to make a dent in that shortage. In 2018 and 2019, the Chicago Department of Housing’s multifamily construction and rehab programs, along with its Low Income Housing Trust Fund, supported 2,732 households, while private developers fulfilling requirements to create affordable units produced 511 units.

The crisis could eventually draw more private investment into the affordable housing sector, experts say. Massive market-rate developments, especially ones near the dense Central Business District, have lost some of their prestige as renters abandon urban cores in favor of outlying properties, and investors may increasingly see affordable housing developments with rent subsidies as more stable.

But addressing the greater need for affordable housing to deal with the pandemic fallout will be far more uncertain if federal stimulus dollars don’t start flowing. Hamer and other stakeholders say both greater subsidies and expanding the amount of tax credits available for private investors are needed. But with control over the U.S. Congress likely to be divided, Hamer isn’t optimistic.

“The way things look right now, it’s a steep hill to climb,” he said.

Private investors could provide a lifeline. Jaeger said his firm has a portfolio of more than 13,000 apartments nationwide, including more than 9,000 affordable units. And its work, which typically involves using Low-Income Housing Tax Credits to attract investors and then acquiring and renovating affordable properties, isn’t slackening.

“Investors right now are eager to get into affordable housing,” he said. “It’s a little counterintuitive, but now is the time for expansion and growth.”

Rents for luxury housing properties in or near the downtowns of Los Angeles, Seattle and many other cities are down, in some cases 20% to 25%, Jaeger added.

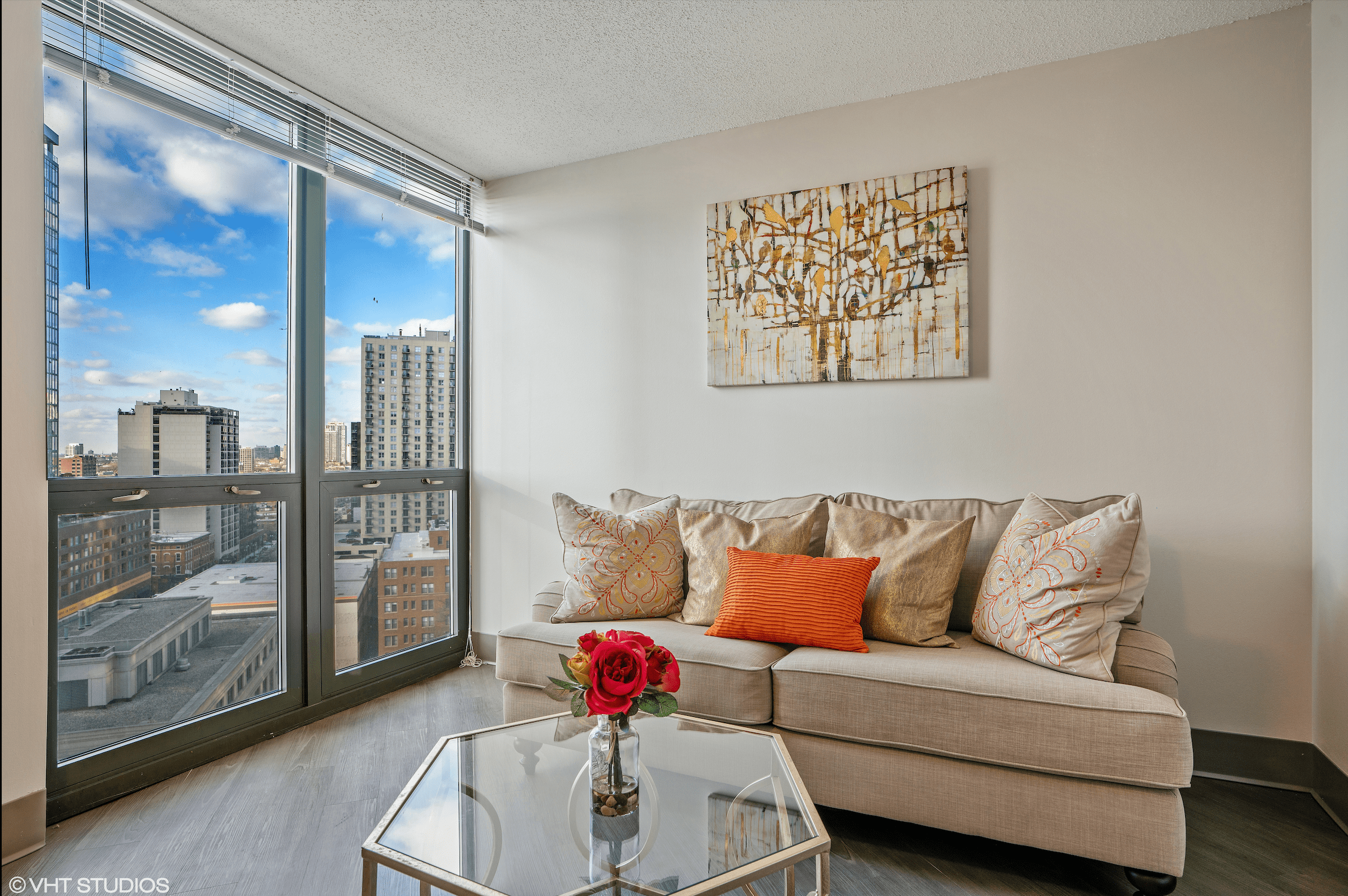

In downtown Chicago, multifamily occupancy fell from 93.8% one year ago to 87.1% in Q3, according to a report in Crain’s Chicago Business, citing data from Integra Realty Resources. During the same period, landlords cut rents between 18% to 23%, depending on the submarket.

Affordable housing developments, by contrast, frequently have units supported by Section 8 vouchers or are rented by residents that until recently were getting federal payments meant to relieve distress caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

“The delinquency rates for affordable housing have been lower, and occupancy rates higher, than in market-rate communities,” Jaeger said.

Investors have taken notice.

“Our acquisition pipeline has never been busier,” he said.

Standard Cos. closed in November a $31M deal that used tax credits to preserve the 61-unit Villa Raymond Apartments in downtown Pasadena as affordable housing for another 55 years, as well as do a $5M renovation. The firm closed a total of about $100M in transactions in the last six months, and Jaeger expects another $100M by the end of 2020, with $200M already in the pipeline for next year. That includes a deal with the Illinois Housing Development Authority for an affordable housing property in Chicago.

POAH’s Eager said investor interest has played a role in protecting the affordable housing industry from the same decline as market-rate multifamily.

“The prices they’re willing to pay for these tax credits has remained stable,” he said.

Eager’s group began renovations in August at the former YMCA at 3039 East 91st St. in the South Chicago neighborhood, and it plans to preserve its 101 units as affordable senior housing. Along with its partner Claretian Associates, a neighborhood community group, POAH financed the deal with Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, tax-exempt bonds, a $1M loan from the Illinois Housing Development Authority and a $4.6M loan from the city of Chicago’s Department of Housing. The project was one of several POAH did this year on the South Side of Chicago, and for next year, the group already has deals lined up for properties in Chicago, Elgin and Harvey.

“Our business is at anything but a standstill,” Eager said.

Still, there’s no guarantee that interest will remain stable if the economy keeps getting shocked by the coronavirus.

“We’re worried about how our industry will be affected until we get to the other side of this,” Eager said. “I do know the market is still robust, construction continues and obviously the need is there.”

To sustain investment, Jaeger said Chicago and the state of Illinois should consider expanding the use of tax incentives for investors willing to finance affordable housing. Other states such as California established far more extensive tax credit programs to create and preserve affordable housing, Jaeger said, including the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee, part of the state treasurer’s office, which will disburse $500M in tax credits this year.

“That really helps ramp up the pipeline and boosts the ability to create additional product,” Jaeger said.

Hamer agreed more incentives could be important for the Chicago region, considering the financial straitjackets that constrain both the city and state. And the migration of so many people away from market-rate multifamily into homeownership would also help bring the investment needed to expand the region’s affordable housing supply.

Chicago’s homeowners grew over the past decade from 48.9% of the population to 50.4%, according to a new study by RENTCafé. During the same period, the city’s renter population declined by 3%.

“As developers look at those trends and see the consistent demand for affordable housing, hopefully more will get their arms around the idea that affordable housing would benefit their business,” Hamer said.

But he isn’t too optimistic either the state or city will become more generous with targeted tax incentives. Hamer pointed out that one of the ways Lightfoot’s administration is balancing its 2021 budget is with a property tax increase.

“We’d love to get a write-down on land for affordable housing,” he said. “But can the city afford it now? Right now, I can’t see that happening at this point in time.”

Even if such investment tools materialize, it would take builders and investors years to use them to create more housing. And the city may have a more immediate affordable housing crisis at hand, according to Stacie Young, director of The Preservation Compact, a program of the Chicago-based nonprofit Community Investment Corp.

The group helps finance the preservation of existing affordable housing, most of which is owned by small landlords. Their renters were sustained throughout much of the year by payments authorized by the CARES Act, in addition to jobs protected by federal loans for beleaguered businesses, she said. Now that these funds have largely run out and Congress hasn’t yet authorized more resources, small landlords will likely see their rent collections fall.

“If the rent doesn’t flow, these buildings will fail,” Young said. “If we don’t see that kind of relief, there will be consequences.”

“Obviously, the city’s budget matters a lot, but it’s more important what happens at the federal level,” Eager said.

Young agreed.

“To expect the city to come up with that kind of money is outrageous,” she said.

“It’s not a bleak picture,” Hamer added. “But it’s important the federal government, as well as the state, county and the city of Chicago, acknowledge the problem and focus resources on the preservation and creation of more affordable housing.”