The preservation of existing buildings — either via renovation or conversion into new uses — is of particular significance when it adds to the supply of much-needed affordable housing. Doing so requires owners and project partners who are committed to restoring affordability as opposed to upgrading a property to market-rate housing.

“There’s such a shortage of affordable housing to begin with that to be able to provide that use for families or individuals to have a place to call home and a place they can be proud of — that’s part of the purpose here,” says Mike Krych, senior partner at architecture and design firm BKV Group. “Secondly, when that place is of historic significance, it’s even neater to call it home.”

Most of these affordable housing renovation projects are financed via the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Properties of historical significance are also eligible to receive state and federal historic tax credits.

BKV recently completed the design for the redevelopment of the historic Fort Snelling Upper Post in St. Paul, Minnesota, into afford-able housing. The post served as the point of departure for thousands of Minnesota soldiers during the Spanish American War, World War I and World War II. It also housed a Japanese language school for the U.S. military from 1944 to 1946.

Developer Dominium is in the final stages of securing tax credits with the State of Minnesota and the National Park Service, then construction will commence shortly thereafter, according to Krych. The property’s 26 buildings, dating back to the late 1800s, will become affordable housing units of various sizes.

One of the greatest challenges associated with the transformation of existing buildings is determining whether building systems that have reached the end of their lifespan can be replaced, says Jeffrey Head, vice president of development for The Habitat Affordable Group, the affordable housing division of Chicago-based developer and manager The Habitat Co. “This is a particular challenge for a LIHTC rehab because there are minimal opportunities for new cash infusions during the required 15-year hold period.”

If there are residents living at the property, the other main challenge is completing the rehab project in a manner that minimizes disruption to tenants, says Head. “This requires a coordinated communications program that pre-pares residents for the scope and timeline of the program and informs them of the benefits and obligations.”

Layers of Financing

One historic project underway involves the renovation of Carl Mackley Houses, a 184-unit affordable housing complex in Philadelphia that opened during the Great Depression era. WinnCos. recently closed on the acquisition of the property and plans to implement a $23.7 million renovation and preserve the community as affordable housing. It took two-and-a-half years to cobble together all the layers of financing needed, according to Amy McHale, vice president of WinnDevelopment. Adding to the challenges was the mandate by local housing authorities that central air conditioning be added, a very costly endeavor for a property of this age.

Tax-exempt bond financing and 4 percent LIHTC from the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency financed the majority of the project. Additionally, since the property is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it qualified for federal historic tax credits. There were also state historic tax credits, subordinate debt from the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority and energy retrofit dollars from Philadelphia Gas Works, according to McHale.

Construction began a week after the financing closed in April. The renovation is expected to take 18 months. While residents’ units are being renovated, they have the option to either stay in a hotel or move in with a family member and receive an allowance. Most residents will only be displaced for two to three weeks, but some units will be updated to be fully compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act, which will take approximately six weeks, says McHale.

In addition to installing central air conditioning in all units as part of the rehabilitation effort, the developer will modernize apartment kitchens and bathrooms in four buildings, replace all windows and roofs, and upgrade common areas.

The Carl Mackley project is a quintessential example of affordable housing preservation, says McHale. “The property was facing significant capital needs requirements, and it’s always less costly to preserve existing buildings than it is to build brand-new ones,” she says.

Project costs for Carl Mackley, including the acquisition and rehab, total roughly $220,000 per unit, whereas new construction typically ranges from $300,000 to $400,000 per unit, says McHale.

With new construction, unknown factors such as subsurface conditions can be more difficult to assess and therefore make exact costs more challenging to determine, adds Larry Curtis, president and managing partner of WinnDevelopment. Additionally, land may be scarce and expensive for new construction.

“These properties offer acquisition and rehabilitation opportunities in which we can lock in affordable housing subsidies for the long term at a fraction of the cost of building new,” says Curtis. “The acquisition-rehab approach combats the gentrification and displacement often associated with value-add rehabs that try to move properties toward market-rate positioning.”

Since 2015, Winn has overseen the completion of 22 occupied rehabilitation projects totaling more than 3,400 units across six states and Washington, D.C. The total development costs for those projects were nearly $500 million.

Utilize Available Resources

In April, The Michaels Organization completed the rehabilitation of West Baltimore’s Rosemont Tower in partnership with the Housing Authority of Baltimore City. The project was a Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) con-version of a former public housing building. According to HUD, the RAD program enables public housing agencies to leverage public and private debt and equity to reinvest in the public housing stock. Units move to a Section 8 plat-form with a long-term contract that must be renewed in perpetuity, ensuring the units remain permanently affordable.

Rising 13 stories with 203 units, Rosemont Tower is home to seniors age 62 and older as well as non-elderly people with disabilities. The renovation project, which had a total development and acquisition cost of $51.2 million, was funded mainly through 4 percent LIHTC and a HUD loan, according to Curtis Adams, vice president of development with Michaels.

The property was built in 1983 and had received essentially no renovations since then, says Adams. “The building’s mechanical equipment was inefficient and outdated, posing concerns they would give out before we were able to replace them. Water lines running up the entire 13 floors were in poor shape and leaking in many places, requiring replacement,” he says.

The RAD program was essential for the longevity of Rosemont Tower, argues Adams. “The property’s operating expenses with respect to utilities and repairs of outdated equipment had increased to an unsustainable amount,” he says.

In addition to making the necessary building repairs, Michaels also modernized the main entrance and lobby area and replaced all the appliances in each unit.

Sense of Community

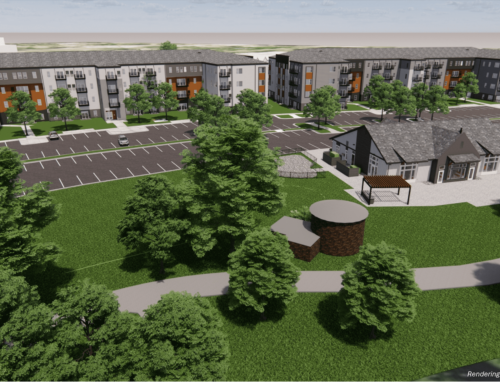

Standard Communities, the affordable housing division of Standard Cos., recently closed on the acquisition of Bridgeview Village Apartments in Charleston, South Carolina. Built in 1971 and acquired via a long-term ground lease, Bridgeview Village is a 100 percent affordable housing community comprising 300 units with-in 26 buildings on a 22-acre site, according to Tommy Attridge, Standard’s director of Southeast production based in Charleston.

“The property had undergone a renovation in the early 2000s, but had not been substantially touched since then, so we saw a great opportunity to preserve and renovate it,” says Attridge. “This is the largest privately owned affordable housing community in the city of Charleston.”

The acquisition had a total capitalization of more than $97 million, including a $22 million renovation. Alliant Capital provided LIHTC equity in a transaction arranged with the South Carolina State Housing Finance and Development Authority and Housing on Merit. Citibank provided additional funding.

All units at Bridgeview Village are covered by a Section 8 Housing Assisted Payment contract from HUD. Residents pay rent at 30 percent of their income and the balance of rent is covered by HUD.

Standard expects to spend approximately $70,000 per unit to upgrade unit interiors, including flooring, countertops and cabinetry. Standard will also build a resident amenity center. The project is underway and will likely take two years to complete, according to Attridge.

“Here we felt that establishing a sense of community by having an amenity center would be key to resident success and engagement, and making it feel more like a neighborhood as opposed to a fragmented apartment complex,” says Attridge. “The site has tremendous potential, and we plan to own for the long term.”

Attridge says that Bridgeview Village aligns perfectly with Standard’s acquisition strategy of targeting well-located properties within cities that are in need of affordable housing. Standard has completed more than $2.6 billion worth of affordable housing acquisitions and rehabilitations across the country.

Almost every article or study you read in almost every jurisdiction says there is a dramatic need for affordable housing,” says Attridge. “We’re just trying to do our part.”

Originally published in Southeast Multi-Family & Affordable Housing Business May/June 2021 Issue